SME IPOs: How they are rigged and why in September?

MH, as we will call him to protect his identity, has been a dealer in the small and mid-enterprise (SME) space for almost a decade.

The market regulator, on September 25, placed this segment under Additional Surveillance Measure (ASM) and Trade-to-Trade (T2T) settlement because there were concerns that volumes and prices of these scrips were being manipulated and that these scrips were then dumped on retail investors.

It wasn’t news to MH. He knows how this works to its last detail. As he tells Moneycontrol, “Koi bhi kachra company SME listing ke liye aa sakta hai” He estimates that an SME IPO can be rigged with a few thousand applications, with one large operator who has over 50 smaller operators in their network, especially in Mumbai and Ahmedabad.

Starting right

A decade back, in 2012, the National Stock Exchange and Bombay Stock Exchange introduced the BSE SME and NSE Emerge platforms to provide a sustainable option for smaller companies to raise equity capital. The intentions were right, but sadly, most small and medium enterprise (SME) IPOs today have allegedly become a way for promoters to collude with operators, inflate prices and then dump the stock on retail investors.An essential step here is botching the entire IPO subscription process - because higher subscription numbers usually mean a good listing premium.

It is a highly secretive business but MH, good-naturedly, gives us a guided tour.

Why September?

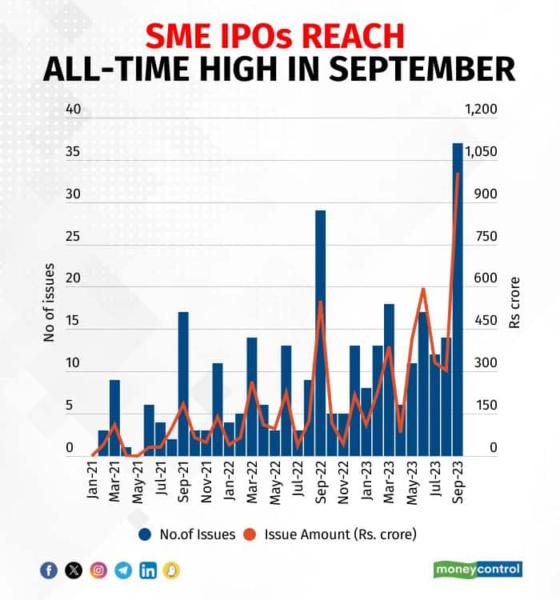

First, he calls our attention to the surge in SME IPOs in September. A record number of micro, small and mid-sized enterprises went public last month, with 37 companies raising more than Rs 1,000 crore, the highest since SME IPOs began in 2012, as per Prime Database data.

“Why do you think that is,” he asks, rhetorically, and then answers his own question. It’s about a deadline that SMEs can’t afford to miss. If they do, their compliance requirements can go up three-fold.

He explains that SMEs are required to declare results once in six months, unlike mainboard companies that are bound to do it every quarter.

If the September 30 deadline is missed, SMEs will have to update the prospectus with the half-year financial numbers. These numbers should be filed first with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, then with the exchange and thirdly with the market regulator, SEBI.

Before September 30, the paperwork needs the clearance only of the exchanges. SMEs IPO prospectus does not require SEBI approval, it only needs the approval of the exchange on which the company wants to list. There have been cases where the public issue has been approved within two days of filing the papers, says MH.

“SME companies file the final prospectus with SEBI for reference only… just for the books, that too, after the IPO process is completed,” MH says. Without the regulator’s eye, most numbers are laxly reported.

That’s why, says MH, “by hook or crook, the promoters try to get a listing approval before September 30”.

Also, this laxity in reporting numbers serves well to create an exuberance at the time of listing. For example, by not disclosing any order win received in the April-September period in the prospectus, but at the time of the listing.

How is it done?

Here’s "how" the IPO rigging happens.

It starts with the promoters, of course. They make a simple request: Get X number of applications for the public issue; and the main operator passes it down to other smaller operators. The main operator is promised the bulk of the profits made and the smaller operators take a 20 percent cut.

The operators then scurry to look for IPO "applicants", who apply only to sell their applications.

These applicants will be compensated in two ways—either through "subject to" or through a fixed cost.

In the first method, the deals are done in the range of Rs 10,000 – Rs 15,000 per application. Here, the investor sells his/her application to the operator to receive the amount, but only subject to allotment of shares. Once allotted, the shares have to be sold during the pre-open session and the investor is guaranteed to pocket Rs 10,000 in cash.

There’s a catch here.

MH explains that the "subject to" method makes sense only when the listing happens at par or at a slight discount. In case the shares list at a significant premium, then the investor is at the losing end because all the profit on the application amount is pocketed by the operator and the investor gets only the assured Rs 10,000.

Also Read: Little giants growing an ugly head? Mapping the exuberance in the SME segment

Let’s break this down further. Suppose the issue price is Rs 60, one lot is 2000 shares, then the application amount is Rs 1.2 lakh. The shares list at Rs 120, indicating a 100 percent gain. Since the investor has sold his/her application to the operator, the operator gets the entire profit – that is Rs 1.2 lakh - and the investor gets only Rs 10,000. Furthermore, the tax implication on the sale of shares comes on the investor’s books.

In this "subject-to" method, if the investor does not get allotment, then there’s no deal.

The second method "fixed cost" does not have this caveat.

Here, investors are assured Rs 2,000 per application from the operator, whether they get allotment or not. However, investors cannot get away with filing a bogus application. “Operators get in touch with registrars to ensure that investors’ application is a valid one, not filled by a third-party agent and does not get rejected due to a wrong PAN or Aadhaar number. The amount is transferred only after this is ensured,” MH says.Here, the investor walks away with Rs 2,000 after selling the application and is not bothered with the allotment process. The operator, in cahoots with the registrar, then tries to make sure that about 40-50 percent of "fixed cost" applications definitely get allotment so that he pockets all the listing gains while his outgo in cash is much lesser than the first method.

All of these deals are made with a handshake and leave no paper trail.

Wait, this is only till the "sell" side of the story. So who is buying these inflated scrips?

MH says that these are some high networth individuals (HNIs and qualified institutional buyers (QIBs) who are willing to take a loss on their books. “These HNIs and QIBs might have realised huge gains in some other deal. So they are okay with taking a loss here to offset huge tax payments.”

Many market insiders seem to know that these games are widely played. A merchant banker, on condition of anonymity, tells Moneycontrol that listing gains are mostly artificial, yet retail investors are being sucked into this vortex of exuberance. The investors aren’t deterred by the SME application prices which can go up to Rs 1 lakh.

“In comparison, one application for mainboard IPO is worth Rs 15,000-Rs 20,000 only,” he says.

Nevil Savjani, Co-founder, Beeline Capital Advisors sounds aggrieved. He tells Moneycontrol that a few SME companies are making the case difficult for the entire industry.Beeline has been the lead manager of 16 SME IPOs so far in the calendar year 2023. To stay away from the bad apples, Beeline has a strategy in place. “We do not sign mandates with companies having net profit of less than Rs 5 crore. We also check whether the past financial performance of the company shows a growth runway of 25-40 percent in the next few years.”